When I picked up Lois Lowry’s Newbery-winning novel The Giver for a re-read, I was reminded of something that the author C.S. Lewis once said: “No book is really worth reading at the age of ten which is not equally (and often far more) worth reading at the age of fifty.” I am often struck by the truth of this statement when I re-read classic works of children’s literature, especially when I return a book that I haven’t touched in at least a decade. The memories of a novel come rushing back; the significance that the story held for me in my childhood intermingles with my “adult” reactions, adding layers to the experience of reading the book. Lewis’s quote came particularly into my mind as I re-read The Giver, since I have actually experienced the death of loved ones and wrestled personally with some of the questions in the book since last reading Lowry’s novel. Now The Giver is no longer just a well-written work of dystopian fiction in my mind, but also a reflection on events that are personally significant.

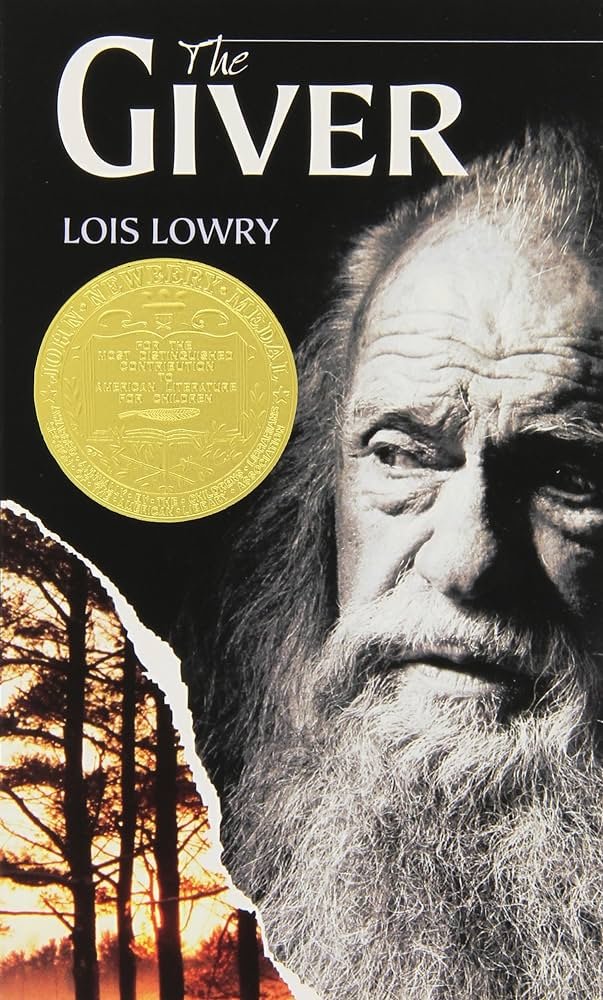

When re-reading, I remembered the basic plot of the novel: twelve-year-old Jonas is living in what seems to be an ideal society where no one experiences pain of any depth. But once he is chosen to be “The Receiver of Memory” for his community, he begins to learn the price of his society’s seemingly idyllic existence. While his friends and peers start training for their new occupations as Doctors, Teachers, Nurturers, and Recreational Assistants, Jonas begins to meet with the current Receiver. The elderly man’s job is now to pass on the memories of their entire society to young Jonas, bestowing the burden of knowledge on the boy. And so the Receiver becomes The Giver of the novel’s title.

Through Jonas’s relationship and work with The Giver, he begins to perceive many new things about the world around him, both beautiful and painful. He learns about many exciting, wonderful experiences of which his family and members of his society are completely unaware. For example, they do not understand the depth of both affection and sexual love that human beings are able to feel for one another because they are medicated to remove sexual urges. His society has sought to eliminate the horrors of physical pain and emotional anguish, but have also robbed themselves of the emotions at the opposite end of the spectrum, such as joy and passion. The Giver must teach Jonas about these things, as well as physical pain and death, and the knowledge and experience of these things will now be his burden to carry in order to shelter the rest of the community from such horrors. But once Jonas realizes how the people of his society have handicapped themselves, he wants to devise a way to restore memories and emotions to the individual members of the community so that they can once again experience creativity, pleasure, joy, and passion.

The society that Lowry has created becomes more and more obviously insidious as the novel progresses. “Sameness” stretches across all aspects of their community: the society dictates acceptable behaviors, occupational choices, spousal selection, and family planning. Everything is masterfully controlled – even climate, genetics, and death.

As I re-read the novel, I was particularly fascinated to notice the community’s use of language; in various situations, there is a prescribed script which the members of this society must follow and so it is through language that the people police themselves and control is maintained. As someone who loves words and phrases and stories, I noticed more and more the ways that the social and individual narratives were controlled: the prescribed apologies and standard responses for every social situation, the use of a number instead of a name when a child misbehaves, a name designated as “Not-to-Be-Spoken” if a person of that name has been a particular disgrace, the required family ritual of dream-telling, the importance that is placed on the precision of language – and Jonas’s resulting preoccupation with the accuracy of his expressions. All of these things create parameters for the individuals of this society, which shows just how powerful language and narrative can be. The creators of this society felt that they must standardize even a simple apology in order to ensure safety and happiness.

It is obvious that while this “sameness” was intended to provide safety and happiness, it has removed people’s free choice and the vibrancy of their lives. Yet upon re-reading The Giver at this juncture of my life, I must admit that there were certain aspects of this society that appealed to me. Just the year before re-reading this novel, I watched both of my very special grandparents rapidly deteriorate physically, then die – and so it seemed somewhat attractive to me that in this society, the elderly were treated with so much respect, cared for so diligently, made so comfortable, then “released” before they started to suffer. Euthanasia is a touchy subject – one of many in The Giver. Lowry does not shy away from portraying this and other taboo topics and reading the novel again, I reflected on just how complicated many of these issues can be.

But The Giver does not attempt to preach – it simply presents these very complicated social issues in a context that allows readers to see the trade-off. There are reasons that this society has relinquished many of their rights – and in certain ways, they are better off. I don’t think that they just seem to be better off – they are better off. It is not a total illusion. Everyone has a stable and supportive family life, a warm and comfortable place to live, plenty to eat, good medical care, and a role in society that they understand. But ultimately, we have to ask ourselves, is the trade-off worth it?

This website was created with a lot of love, Coke Zero, and tacos by Kumquat Creative.