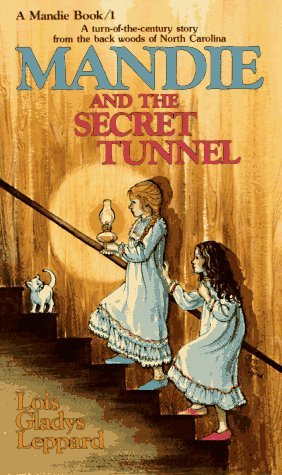

It had been something like twenty-five years since I first read the Mandie books by Lois Gladys Leppard when I discovered the series had been published on Kindle. I already remembered some of the characters well, such as Mandie’s handsome friend Joe Woodward, her Uncle Ned the Cherokee Indian, and her kitten Snowball. But as I re-read Mandie and the Secret Tunnel, the first volume in the series, my memory of other series characters was also quickly revived, including Mandie Shaw’s neighbor Polly, the servants Aunt Lou and Liza, Uncle John, Elizabeth Shaw, and Mandie’s Grandmother Taft. Rediscovering all of these characters felt more than a little bit like coming home. And the plot is a rollicking good time, with an orphaned heroine, secret tunnels, missing wills, ghosts, a Cherokee spy network, and long-lost relatives. It seems a lot like a Nancy Drew novel, in fact.

Of course, a few decades after first reading Mandie and the Secret Tunnel, my critical analysis skills have been sharply honed by graduate school and a professional career. I noticed several problematic and upsetting aspects of how race is depicted in the novel that had gone right over my head when I was a child.

For example, although Mandie comes from a poor family in Charley Gap, North Carolina, Leppard depicts her as the epitome of white privilege. Mandie’s father Jim Shaw and his brother John are part Cherokee Indian, making Mandie one-quarter Cherokee, a fact that Mandie is thrilled to find out. Uncomfortably, she quickly begins referring to the Cherokees as “my people,” something that seems glib and disconcerting coming from a blonde white child who seems to have been largely sheltered from conflict between whites and indigenous people while living in the backwoods of North Carolina. In early 20th century society, Mandie’s white skin and head full of shining blonde hair place her above African Americans and Native Americans, even before her ties to her wealthy relatives are revealed partway through the novel. While Mandie and the Secret Tunnel acknowledges that some white people are “out to kill every Indian they could find,” most of the time, Mandie and her friends act as though they don’t need to consider the tensions between white people and Native Americans. Despite her friendship with many Cherokees. Mandie often doesn’t think about the potentially serious consequences of her actions, which would certainly have greater repercussions for characters of other ethnicities.

In fact, in Mandie and the Secret Tunnel, Uncle Ned and his fellow tribe members seem to exist just to protect Mandie and carry out Jim Shaw’s bidding from beyond the grave. Prior to the start of the novel, Mandie’s father and Ned Sweetwater have a particularly close friendship, and so Ned promises Jim Shaw that he will look after young Mandie. After the death of her father, Uncle Ned becomes Mandie’s secret guardian and a close father figure. A friendship also later forms between Mandie’s Uncle John and Ned, drawing the whole Shaw family even closer together with the Cherokee characters. But when Mandie convinces Uncle Ned to help her run away from Charley Gap to look for her mother’s relatives in Franklin, North Carolina, Mandie doesn’t seem very concerned about the fact that had Ned and his fellow Cherokees been caught spiriting Mandie away from her home, they would have been strung up by a posse, even though they were planning to take her to live with her Uncle John. Mandie and the Cherokees have to hide from posse members, so while on the journey, Mandie realizes that there would be negative repercussions if they are caught. But she conceptualizes the consequences only in terms of what it would mean for her – that she would have to go back to the horrible adoptive family from whom she is trying to escape. I suppose that Leppard might have thought it would be too gruesome for her twelve-year-old protagonist to imagine a lynching.

I was also horrified to discover how the novel/series depicts Native Americans overall. All of the indigenous characters speak in stilted English and the narration states that the Cherokee Uncle Ned’s “pronunciation is good,” it’s just “his grammar [that is] poor.” Ned is the most prominent Cherokee character in the novel/series, the only indigenous character that is even given much of a voice. But although Mandie’s relationship with him is portrayed in a positive light, Uncle Ned is never developed as a character. In novel after novel, he remains a mysterious, almost magical figure who appears at Mandie’s window at night to dispense Cherokee wisdom and helps Mandie out of tough spots. Although he’s a “good guy,” he’s not portrayed as a three-dimensional human being (even by the standards of this rather cliché children’s series). While it seems like Leppard may have been trying to progressively portray indigenous characters in the series, I feel like she could have done a much better job. Or maybe I’m expecting too much for a book that was written in the early 1980s, which also gave us such children’s stereotype-filled classics as the Indian in the Cupboard series by Lynne Reid Banks.

But at least Mandie and the Secret Tunnel focuses directly on indigenous characters and openly acknowledges the tension between the Cherokees and whites. Meanwhile, Leppard hardly acknowledges the position of African Americans during the time that the novel is set, which is even more problematic and upsetting in my opinion.

The novel is set in 1900 in North Carolina, and although slavery was abolished in 1862 with Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation (or in 1865 when Lincoln signed the 13th Amendment, depending on your perspective), African Americans were still locked into a social structure that degraded them at every turn. The year 1900 was just four short years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that Jim Crow segregation laws did not conflict with the 13th and 14th Amendments, upholding the practice of “separate but equal.” African Americans lived their lives at a great disadvantage to whites and under the constant threat of violence. Lynchings were prevalent in the south.

Despite this brutal reality, when Mandie goes to live at her Uncle John’s house in Franklin, she immediately meets a group of African American household servants who are trivially characterized as happy and even carefree. Over the course of the series, these Black servants become a regular part of her life but their treatment is continually glossed over. The stereotype of the “happy darky” was used to romanticize slavery and Jim Crow in post-War fiction with sickening effects, and the presence of such an insidious trope in Mandie and the Secret Tunnel is very upsetting.

In the novel, the household is run by the jovial and motherly Aunt Lou, who oversees the cheerful servant girl Liza and Jenny the cook. A fourth servant named Abraham is also briefly mentioned. While race isn’t explicitly referenced, the speech patterns of all of the servants characterize them as stereotypical African Americans. They are depicted as being separate from the white members of the household, but content and pleased to be looking after their white masters. In particular, Aunt Lou and Liza immediately take a strong liking to Mandie. Aunt Lou begins calling Mandie “my child” and dressing her up in pretty new clothes like a china doll, while Liza delights in washing and combing Mandie’s hair. Of all the characterizations of the African Americans, Liza’s is the most irritating. As she “twirls” and “spins” and “dances” in and out of rooms, Liza seems happily and whimsically content to perform household chores while Mandie and Polly, her white peers, are free to spend their days playing detective. She is the epitome of the “happy darky” trope, portraying African Americans as happy within the confines of slavery and neo-slavery/servitude.

And so even though I was nostalgically enjoying the plot, the depictions of race and white privilege in Mandie and the Secret Tunnel soured my experience of the novel. (And I haven’t even explored Leppard’s problematic depictions of Christian faith.) For these reasons, I would definitely have to think long and hard before giving this novel/series to a contemporary child to read. When looking back at my favorite childhood classics to share with my four nieces, I would much rather give (and already have given) them the Nancy Drew novels. While Nancy Drew also contains problematic depictions of race, the stereotypical ethnic characters have a far less prominence in the stories. The omission of significant characters of color is an issue to discuss with children in and of itself, but it’s much easier to talk about the negative depictions of ethnic characters and still enjoy the story when the book is not completely saturated with negative racial depictions. I honestly am not even sure how I feel about continuing to re-read the series myself at some point. The nostalgic part of me would love to dive back into some of the other Mandie mysteries, but I wonder if it’s truly worth my time. In the 2020s, there are plenty of well-written middle-grade and YA mystery novels that do a much better job at portraying characters of different races and cultures.

This website was created with a lot of love, Coke Zero, and tacos by Kumquat Creative.