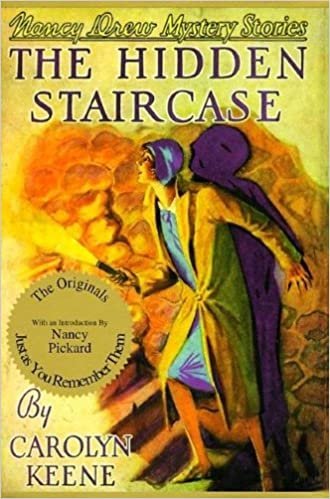

Note: this is a review of the ORIGINAL version of The Hidden Staircase, published in 1930. Want to know the plot differences between this story and the revised version that was published in 1959? Check out The Hidden Staircase Wikipedia article.

In The Secret of the Old Clock, the first volume of Mildred Wirt Benson’s original Nancy Drew novels, readers met a feisty sixteen-year-old sleuth who was ready and willing to face off with a gang of inebriated thieves. Alcohol in a Nancy Drew novel? Shocking! But in volume two of the series, The Hidden Staircase, things get even better – Nancy is locked and loaded!

In the original novel, Carson Drew gives Nancy his revolver to keep with her when she goes to stay at the haunted Mansion with Floretta and Rosemary Turnbull. This is the first sign that this version of the story is a lot more exciting (and violent) than the revised “yellow spine” edition. Nathan Gombet, the villain in both versions of the novel, has an open confrontation with Nancy in the first chapter that is considerably toned down in the revised edition. Arguing with Nancy, Mr. Gombet openly accuses her father Carson Drew of being crooked and cheating him out of a great deal of money. Mr. Gombet is quite physically threatening, and then both he and Nancy lose their tempers. Gombet almost hits Nancy, but she gets a table between them and grabs the telephone, threatening to call the police if he doesn’t leave the Drew house immediately. Throughout the novel, Gombet continues to be portrayed as an unscrupulous and sinister man, a characterization furthered by his creepy taxidermy hobby. When in his house, Nancy encounters a room of both stuffed and live birds. Nancy notes that the birds are “a gruesome sight” (141) and calls the room a “chamber of horrors” (148). Being an ornithophobe, I completely agree – a room of stuffed birds is positively creepy! If I were planning to face off with a man like Gombet, I would want a gun too, a sentiment which leads Nancy to this amusing line of thought: “I think Dad was wise to suggest that I take his revolver,” she told herself. “And I’ll take plenty of ammunition, too! Enough to annihilate an army! Though, truth to tell, I don’t know whether I could hit the broad side of a barn or not” (65). For better or worse, Nancy sleeps with the revolver under her pillow each night and takes it with her when she breaks into Gombet’s house. (Yes, our heroine engages in breaking and entering – something else that is eliminated from the revised version.) There are so many scenes with guns in this novel, including the climax of the novel which involves a sawed-off shotgun standoff, that The Hidden Staircase began to remind me of a Hardy Boys novel.

The increased tension and excitement that run throughout the novel are especially prominent in the scene when Nancy discovers the hidden staircase named in the title. Although Nancy’s discovery of the staircase and the connected underground passageway is tense in the 1950s version, the overall tone is a sense of excitement as Nancy and the reader both wonder what she will discover. But in the original version, Nancy’s trip down the secret passageway more tense, prolonged and dramatic, written with a much more ominous tone. She is already a prisoner in Gombet’s house, locked into the taxidermy/bird room by Gombet’s suspicious servant. Although Nancy is desperate to escape from the bird room, her discovery of the secret door seems to put her in even more danger because she plunges down the stone steps into the dark and hits her head, remaining unconscious for quite some time. (In the revised yellow spine version, Nancy discovers the entrance to the passageway that is located on the Turnbull property instead of the entrance in Gombet’s house and so she isn’t in any immediate danger. She falls down the stairs, but isn’t knocked unconscious.) In the 1930s version of the story, the door to the secret tunnel has shut behind her and she can’t find the mechanism to open it again, so Nancy is now trapped not just in Gombet’s home, but “in the subterranean passage [where] cries for help would never be heard” (154). The episode in the tunnel takes more than a chapter, with Nancy encountering rats and her flashlight giving out, whereas the yellow spine edition only devotes a few pages to Nancy’s time in the passageway. (Although the 1959 editors seem to have realized that by considerably shortening this portion of the novel, they have removed a great deal of the excitement and inserted a completely new scene in which Nancy climbs across a roof to investigate a possible secret entrance to the Turnbull mansion.)

While I generally prefer the more exciting, tense pace of the original version of the novel, I have mixed feelings about the portrayal of women in both versions. In the original novel, spinster twin sisters Floretta and Rosemary Turnbull are being harassed by a “ghost” who is haunting their family house and driving them from the only home they have ever known. Floretta is characterized as extremely nervous and anxious overall, and she is quickly convinced to sell the mansion in order to be free of the stressful situation, while her sister isn’t willing to give in and sell their family home. The characterization of Floretta is rather annoying, and sadly, both sisters come off as largely uninteresting and flat. In the yellow spine version, the sisters are changed into an elderly mother and daughter, the great-Aunt Rosemary and great-grandmother Miss Flora of Nancy’s good friend Helen. I suppose that by remaking their familial relationships, the editors were able to remove the “spinster” label and the accompanying negative connotations, which is certainly preferable. I additionally like that they completely transform Miss Flora into a plucky eighty-year-old woman who refuses to sell her family home. But with the introduction of Helen, who plays a significant role in the 1959 version, the editors also managed worm in a bunch of stuff about Helen getting engaged to be married. There is actually quite a bit inserted into several scenes about Helen’s excitement for her upcoming wedding, which I suspect the editors inserted in order to present a more genteel, traditional young woman as a counterpoint to Nancy, to off-set her independence. The message seems to be: “Yes, capable and independent young women like Nancy Drew exist, but she is unusual, exceptional, a rarity.” They may be dazzling young readers with an independent female role model, but they’re also framing her in such a way that those young women don’t get it into their heads to “try this sort of thing at home.”

And then we’ve got the definite downside to the original version of The Hidden Staircase – racism. The treatment of race is also pretty bad in the first volume of the series, The Secret of the Old Clock. I don’t necessarily feel the need to catalog every instance of racism in these older publications, but I want to highlight the depiction of Gombet’s “negress servant” in The Hidden Staircase because of how her characterization differs from the portrayal of Jeff Turner, the lazy African American caretaker in the first novel. In The Secret of the Old Clock, Turner is depicted as fairly shiftless, with seven children to care for and yet easily wooed away from his responsibilities with the promise of free alcohol. Obviously this is a horrible stereotype, but he isn’t portrayed as villainous. Similarly, when Gombet’s servant first appears in the novel, she is described by many degrading terms like “fat,” “surly-looking,” and even “positively vicious” (132) by Nancy herself. he woman is described as being so heavy that she “waddles” and is called “an ogre.” Then it is revealed that she isn’t just Gombet’s innocent servant, but a criminal accomplice, and her portrayal grows worse. She is, in fact, the surly main player in the standoff with the sawed-off shotgun at the end of the novel, and everyone, including our heroine Nancy, shows an extremely racist disdain for the woman. While this shows contemporary readers the horrible reality of attitudes in the 1930s and cannot simply be ignored, I have to admit that this is a side of my beloved Nancy Drew that I would prefer not to see. It is upsetting to think that with these negative portrayals of quavering spinsters and surly negresses, the novel probably did as much to perpetuate negative stereotypes of women and African Americans as it did to inspire young white women to pursue more independent careers and lifestyles.

Setting those things aside (but not forgetting them), The Hidden Staircase is a fun read that is filled in many scenes with more thrilling tension than the revised version of the novel. This is a case where I genuinely can’t decide which version of the novel I prefer, since they are so different and each contain many details and scenes that I enjoy immensely. If you haven’t read the original Nancy Drew novels, I urge you to wait no longer. Seek out a reprint from the publisher Applewood Books and meet the Nancy who has armed herself with “enough ammo to annihilate an army!”

This website was created with a lot of love, Coke Zero, and tacos by Kumquat Creative.