Back before cell phones existed and women were apt to sit anxiously at home by the phone waiting for news, Nancy Drew went zipping through her Midwestern town in her sporty blue convertible. She would be leaving the scene of a burglary or a supposedly haunted house and going to the local police station – to deliver the evidence she had found in person. Refreshingly, the police appreciated her independent, take-charge nature: “The way you’re building up clues, if you were on my force, I’d recommend a citation for you!” Captain Rossland of Cliffwood tells her in The Hidden Staircase.

Though at the beginning of the mystery, he is apt to tell Nancy things like, “I doubt that there is anything you can do. You’d better leave it to the police,” Captain Rossland soon learns to take advantage of Nancy’s many talents, imploring the “girl detective” to question the suspects that the police have been unable to break. “You may not know it, but you’re a very persuasive young lady. I believe that you might be able to get information out of both Harry and Greenman, where we have failed,” he tells her.

Of course, Nancy responds with modesty but agrees to try – and succeeds in obtaining a confession from each of the suspects within minutes. She’s both humble and shrewd – both a proper lady and a feminist, in other words. The popular concept of feminism today would consider that to be a bit of a paradox, but I don’t see why intelligence and heroism can’t be paired with good fashion sense and a “feminine” appreciation of beauty.

And this is one of the reasons that I love Nancy Drew novels – because somehow, Nancy manages to be it all, embodying many contradictions and making it look easy. Of course, the ease with which Miss Drew stumbles upon clues, receives the indulgence of the police, and obtains confessions is a bit difficult to swallow if you’re older than ten or eleven. When I reread the Nancy Drew novels now, I have to adopt a determination to ignore all the unlikely scenarios and plot holes, not to mention a willingness to accept all the one-dimensional characters. But when I’m having a hard time in real life and I need a break from “real literature” – stories about people living in poverty-stricken parts of the world or dealing with heartbreak of one kind or another – I pick up a Nancy Drew. She’s at least as good as a super-hero, and maybe even better because she has the time to don a gay party frock and attend sorority dances and other high society events in between excursions to haunted mansions and exotic locations. She’s Bruce Wayne/Batman for the feminists out there who are looking for a good time.

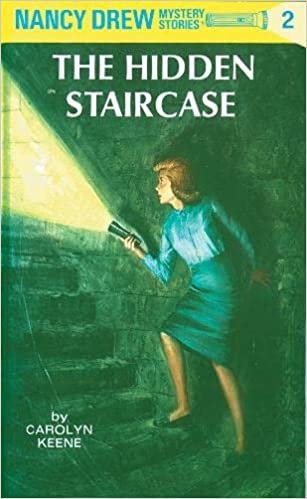

In The Hidden Staircase, which is the second of the original Nancy Drew mystery stories and was first published in 1930, Nancy even gets to solve a case for her father, who is a prominent lawyer, and rescue him when he has been kidnapped by his enemies. After she traipses all over an American Colonial estate, searching for hidden passages and burglars, she discovers where the swindlers have hidden her Carson Drew. And after he recovers from being drugged and held prisoner, the supportive Mr. Drew isn’t embarrassed that his daughter has had to save his skin: “It’s a real victory for you!” Nancy’s father praised his daughter proudly. So you can see that Nancy is lucky enough to live in a world where men respect her and acquiesce to her higher intelligence and innate capabilities. Forget romance stories – this is my kind of wish fulfillment novel!

This website was created with a lot of love, Coke Zero, and tacos by Kumquat Creative.